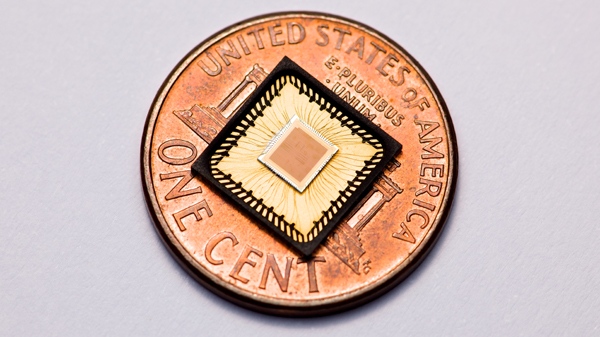

From 2007 to 2011, my startup Lyric Semiconductor, Inc., funded by a combination of DARPA and venture capital, created the first (and so far the only) commercial analog deep learning processor. 440,000 analog transistors did the work of a 30,000,000 digital transistors, providing 10x better Joules/Ops power compared to a digital tensor processing core. This analog tensor processing core was designed as a “plug and play” IP block for use within our digital deep learning microchips. (See this post about our overall deep learning processor architecture.)

We published in ACM1. We also patented early explorations at MIT2, the analog computing unit architecture3, analog storage4, factor/tensor operations5, error reduction of analog processing circuits6, and I/O7, research on stochastic spiking circuits8. We used the terms “factor” and “tensors” interchangeably9.

Our startup was acquired by ADI, the largest analog/mixed-signal semiconductor company in the US, and became the new machine learning/AI chipset division10. Our work also inspired further DARPA work on analog computing11.

There was also significant press coverage: Wired12, The Register13, Reuters14, The Flash Memory Summit15, Phys Org16, The Bulletin17, Chip Estimate18, KD Nuggets19.

The main innovation involved taking advantage of the fact that weights and activations in deep learning models can be represented by (quantized into) 8-bit numbers without causing any issues.

The noise we observed in our circuits, was about 128th of our 1.8V power supply, so we could essentially replace a 7-wire digital bus with a single wire carrying analog current. (In practice we used a differential pair – 2 wires – to represent our analog value more robustly.)

Dropping from seven wires to two wires doesn’t seem like a big enough win to justify the effort of designing analog circuits? Furthermore, the win gets even slimmer if you have decided you can quantize your weights and activations down to two bits. In that case we simply replaced two digital wires with two analog wires! So why bother?

The real win (about 10x in ops per Joule) came from two things:

- You get to use fewer transistors in the multiply accumulate. Instead of a few thousand digital transistors needed to multiply two 8-bit numbers, we could use just 6 transistors. 500x fewer! A 2-bit multiply-accumulate would still require around 100 digital transistors. This is still a 16x win in transistor count for the analog version!

- Less intense switching provided significant additional advantage. On average our analog wires were not switching between 0 and 1, they were varying between intermediate current values.

In the digital version, switching our wires from 1.8V to 0V and back again dissipates the majority of power in our processor. On any given digital wire, this happens about half of the times that the processor’s clock ticks.

By contrast, in the analog version, because of the statistical distribution of weights and activations around 0, on average the currents in our analog wires did not change values nearly as much.

Would all of this still work in a modern 1nm semiconductor chips? One would have to try it to find out for certain, but it’s fairly likely to still work. If the noise floor in chips have not changed very significantly, then dropping the power supply from 1.8V to 0.5V would still provide us with 5 bits of analog resolution to represent weights and activations. 5-bits should still be adequate for today’s deep learning quantization.

In 2010, a small % of the world’s computing workloads involved deep learning. Today deep learning work loads are becoming a driver for global energy consumption. There is talk of deep learning compute consuming the equivalent of dozens of Manhattans. Even less than a 10x win matters even more today than it did then. In addition, we are increasingly interested in deep learning chips within our portable devices, where again a 5-10x could be the difference between an incredibly smart phone and a smart phone of only middling intelligence.

- https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/1840845.1840918 ↩︎

- https://patents.google.com/patent/US7860687B2/en?inventor=benjamin+vigoda&oq=benjamin+vigoda ↩︎

- https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/47/38/f5/1c388a1f370aea/WO2011085355A1.pdf ↩︎

- https://patents.google.com/patent/US9036420B2/en?inventor=benjamin+vigoda&oq=benjamin+vigoda&peid=64758f3a4adf0%3A36%3A7951d761

https://patents.google.com/patent/US8799346B2/en?inventor=benjamin+vigoda&oq=benjamin+vigoda ↩︎ - https://patents.google.com/patent/US9563851B2/en?inventor=benjamin+vigoda&oq=benjamin+vigoda&page=1 ↩︎

- https://patents.google.com/patent/US7788312B2/en?inventor=benjamin+vigoda&oq=benjamin+vigoda&page=1 ↩︎

- https://patents.google.com/patent/US20100281089A1/en?inventor=benjamin+vigoda&oq=benjamin+vigoda&page=2 ↩︎

- https://patents.google.com/patent/US8792602B2/en?inventor=benjamin+vigoda&oq=benjamin+vigoda&page=2 ↩︎

- In a factor graph computing belief propagation, we could have, for example, a softAND gate with incident edges A, B, C. Logically, C = AND(A,B), which yields the tensor or “factor” computation p_C = \sum_{A,B,C} \delta(C-AND(A,B)) p_A p_B.

http://thphn.com/papers/dimple.pdf#:~:text=The%20GP5%20is%20optimized%20to,variables%3B%20as%20a%20result%2C%20complexity ↩︎ - https://www.eetimes.com/adi-buys-lyric-probability-processing-specialist/ ↩︎

- https://www.wired.com/2012/08/upside/ ↩︎

- https://www.wired.com/2010/08/flash-error-correction-chip/ ↩︎

- https://www.theregister.com/2010/08/17/lyric_probability_processor/ ↩︎

- https://www.reuters.com/article/business/the-odds-are-good-that-lyric-semiconductor-will-change-computing-idUS3042405556/ ↩︎

- https://files.futurememorystorage.com/proceedings/2010/20100819_S201_Vigoda.pdf ↩︎

- https://phys.org/news/2010-08-chip-probabilities-logic.html ↩︎

- https://bendbulletin.com/2010/08/18/a-chip-that-calculates-the-odds/ ↩︎

- https://www.chipestimate.com/MIT-Spin-Out-Lyric-Semiconductor-Launches-a-New-Kind-of-Computing-With-Probability-Processing-Circuits/Semiconductor-IP-Core/news/5622 ↩︎

- https://www.kdnuggets.com/2010/08/b-lyric-chip-digests-data-calculates-odds.html ↩︎